Processing the Richard Himber Collection

June 15, 2023

Anna LoPrete in front of the Himber Collection, The Songbook Library & Archives

In May, I, the Songbook Foundation’s Music Librarian, finished processing a large collection that I’d been working on for over six months. The Richard Himber Collection of about 1500 musical arrangements came to us in March 2022.

The Man, The Music, The Magic

Richard Himber (1907-1966) was an American orchestra leader, composer, and arranger. He was also a professional magician. After serving as Rudy Vallee’s secretary, Himber formed his own band in 1932.

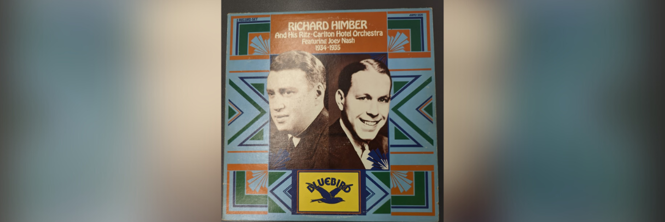

Himber was born in Newark, New Jersey on February 20, 1907. He began playing the violin at the age of 7. In 1929 he became the secretary to the orchestra leader, Rudy Vallee, and booked engagements for Vallee and the singer Russ Colombo. In 1932, Himber formed his own band. Two years later Richard Himber and His Essex House Orchestra were performing frequently in New York City. Also in 1934 Richard Himber and His Ritz-Carlton Orchestra with Joey Nash on vocals recorded the first recording of “Winter Wonderland.” According to the liner notes, Himber may have left the room at the time and was not present for that performance.

His bands became famous for imitating any band in an act called “Parade of the Bands.” He became well-known on the radio in the 1930s, performing on the Studebaker Show, The Eddie Peabody Show, and the Melody Puzzle Show (Lucky Strike). Some of those arrangements are present in the collection.

Himber was also an accomplished magician, performing frequently, and even inventing new tricks and props. In 1962 he was called as an expert witness to exhibit how certain tricks were performed and could be used to trick people out of money, however, an agreement made his witness unnecessary. He was the inventor of numerous magic tricks, some of which are still performed today.

In 1953 he performed a “one-man show with a cast of twenty-eight people” at Carnegie Hall. Perhaps intended as a satire of the one-man show, he described it as “a 4-D production,” containing “droll deceptions, delightfully different.”

In the 1930s Himber was active in music censorship. Along with Rudy Vallee, Paul Whiteman, Guy Lombardo and Abe Lyman, “The Committee of Five for the Betterment of Radio,” met weekly to judge the moral character of the past weeks song. Songs found by the committee to be “objectionable in title or lyrics” were asked to be revised and if they were not revised, they were placed on a list of “banned songs” which was mailed to orchestra leaders across the country. In 1936 he appealed to orchestra leaders to not perform martial music in order to prevent “the recurrence of another great international war.” He wrote that music can “arouse the worst instincts of which civilized man is capable” and “peace-loving citizens can be aroused to frenzy by the savage rhythm of a military air.”

Himber died in New York City on December 11, 1966 at the age of 59.

The Process

The collection came to us in 34 large cardboard boxes holding a mess of arrangements. While most of the arrangements were contained in dilapidated folders, there were numerous boxes of loose parts, and of full scores folded in half and sometimes in half again so they were very brittle. My first step was to create an inventory of all the titles of the scores, arrangements, and parts. With 34 boxes this took a good amount of time. It also left a good deal of paper crumbs on my desk.

Once I had a preliminary inventory it was time to decide how to organize the collection. In the Archives world, we try to respect the original order of a collection. That is, if a person had organized their papers in an intelligent and deliberate manner, we would keep the collection in that order. The Himber collection, however, had come all helter-skelter, there was no discernible order. So it was up to me to determine the order that would be most useful to us and our users. I like the classics, so I went with alphabetical by title.

Putting the arrangements in alphabetical order was arduous. After an hour of pulling heavy boxes off the shelf, just to pull one arrangement and then return the box I realized that this just wasn’t tenable. So we set up the Himber Room, a small office that I lined all four walls with boxes. After this it was a “simple” matter of pulling the arrangements (which sometimes were present in as many as 10 different folders), rehousing them in acid-free folders and labelling them.

Some Complications

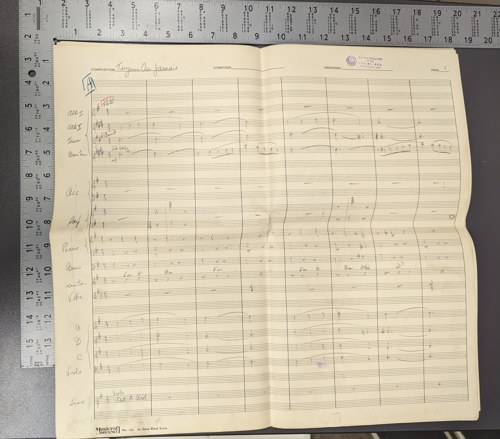

One complication was that Himber frequently had multiple arrangements of the same song. He often had a dance version, a radio version, a record version, etc. And, of course, the scores were separated from the parts. It’s important for users to know what version of the arrangement we have. Do we have just the score, a (sometimes very) large manuscript that shows all the instruments? Or do we have the individual parts as well, a piece of paper that gives just the music being played by a single instrument, say 3rd trumpet? In order to perform an arrangement, you really need both the score and a full set of parts. To determine which score went with which set of parts I compared the notes. All in a day as a music librarian.

Another common complication with collections of music arrangements is that things come in multiple sizes. Parts are on standard 9x12” paper and fit in regular Paige boxes. The scores, on the other hand, can come in any number of sizes of paper. For Himber I used 11x17 and 16x20 boxes but there were a few scores that were too big even for those. In fact, the box we ended up using doesn’t even fit on the shelf.

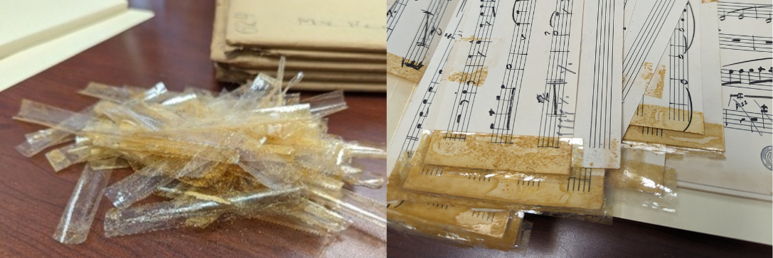

Archives Hot Tape

Oh no! Your paper tore! Think twice before taping it together with Scotch tape. It’s probably fine for your everyday documents if you’re not planning to save them or pass them on to your descendants. But over time it decays, discoloring the paper and separating from it. The Himber collection was covered in tape, nasty, yellow tape that flaked off the paper leaving ugly brown marks behind.

Boxes and Folders, Oh My

The Himber collection is held in 67 archival boxes and 2000 archival folders. Archival boxes and folders are different from regular ones because they are acid-free and won’t decay, causing damage to the items within.

How much do you think it costs to house a collection this size?

- $250

- $1800

- $3600

- $5000

The answer is C, $3600. To assist our preservation efforts, please visit TheSongbook.org/donate

Sources:

“Richard Himber, Band Leader and Noted Magician, 59, Dies.” New York Times, December 12, 1966. Retrieved February 7, 2023, Times Machine.

“Himberama in Switch.” New York Times, October 29, 1953. Retrieved February 7, 2023, Times Machine.

“Himber Troupe to Play Town Hall.” New York Times, September 22, 1953. Retrieved February 7, 2023, Times Machine.

“Himber Asks Orchestras to Ban All Martial Music.” New York Times, Oct. 19, 1936. Retrieved February 7, 2023, Times Machine.

“Song Censorship for Radio Begun.” New York Times, August 15, 1934. Retrieved February 7, 2023, Times Machine.

Lee, William F. American Big Bands. Hal Leonard, 2005.