Of Thee I Sing: Politics on the American Musical Stage

September 14, 2020

"History makes music, and music makes history." - Irving Berlin

Musical theater in the U.S. has engaged with political topics from its early days. From George and Ira Gershwin’s Of Thee I Sing to Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton: An American Musical, the intersection between entertainment, politics, and patriotism presents an emotionally powerful combination for theatergoers.

Some shows are overtly political, addressing social and cultural issues with a heavy hand and a strong message. Others have taken a lighter, more humorous approach to the peculiarities of America’s history and government. And some have been co-opted or taken on a significance that their authors never intended, due to contemporary events happening far from the lights of Broadway.

In true democratic fashion, we invite you to explore the story of politics on the American stage, and to offer your opinions on some of the topics raised by these beloved (or not so beloved!) shows. After you have explored the exhibit, we invite you to cast your vote here in response to the exhibit content. Follow us on social media (@songbookfoundation on Facebook and Instagram and @songbookfdn on Twitter) during the run of the exhibit to see how your fellow visitors have voted.

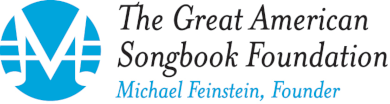

“If you stand for nothing, what will you fall for?”

Hamilton: An American Musical confronts questions of race, immigration, and the American Dream.

In 2015, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton took the theater by storm, with rap and R&B-styled songs, color-conscious casting, and a homage to America as a nation of immigrants. In telling the story of Alexander Hamilton’s journey, Miranda mixed history with hip-hop to create a unique and groundbreaking musical, winning 11 Tony Awards and the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 2016.

Hamilton debuted as the Obama presidency was ending. During an era ushered in by the election of the nation’s first African American president, Miranda reminds us that America has never been a monoculture. Hamilton’s portrayal of the fierce differences between Hamilton, Burr, Jefferson, and others reminded audiences, during a contentious election year, that the path to democracy is often difficult.

"Alexander Hamilton" feat. Leslie Odom Jr, provided to YouTube by Atlantic Records.

In November of 2016, Vice President-elect Mike Pence attended Hamilton on Broadway. During the curtain call, actor Brandon Victor Dixon (Aaron Burr) and his fellow cast members read a prepared statement addressed to Pence as follows:

Vice President-elect Pence, we welcome you … We, sir,—we—are the diverse America who are alarmed and anxious that your new administration will not protect us… or defend us and uphold our inalienable rights, sir. But we truly hope that this show has inspired you to uphold our American values and to work on behalf of all of us. . .

While Pence said that he did not feel insulted by being singled out in this way, President-elect Trump demanded an apology, provoking a storm of social media commentary both for and against his demand.

In addressing VP-elect Pence from the stage, the Hamilton cast made a choice to draw a parallel between the subject matter of the show and political tensions in America on the eve of the Trump presidency.

Do you feel the actors’ action was appropriate?

To cast your vote, visit our online ballot.

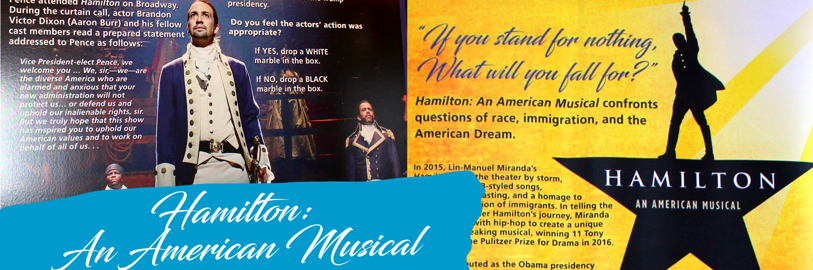

“Of Thee I Sing, Baby!” The Gershwin brothers parody modern American politics in a Pulitzer Prize-winning satire.

After collaborating with George S. Kaufman on 1927’s Strike Up the Band!, George and Ira Gershwin were approached by Kaufman to write the music for another satirical show, this one focused on American presidential politics. The harsh tone of Strike Up the Band (a musical about a war with Switzerland) hadn’t played well with audiences; for Of Thee I Sing, the collaborators took a lighter comedic approach. The musical tells the story of John P. Wintergreen, whose supporters devise a presidential campaign around the platform of “love”—Wintergreen will marry the most beautiful girl in the United States as part of his election campaign. However, Wintergreen opts to wed Mary Turner instead, based on her sterling personal qualities and baking skills. The spurned winner of the beauty contest soon upends the marriage and election, and various hijinks ensue. All’s well that ends well, as Wintergreen’s continually forgettable Vice President marries the beauty queen to save the day.

"Of Thee I Sing" feat. Jack Carson, provided to YouTube by Universal Music Group.

Strike Up the Band was a harsh satire of American protectionism and warmongering; after quickly closing in previews it was extensively re-written for Broadway to remove its darker tone. Of Thee I Sing, several years later, was gentler, with a wink toward back-room politics and clownishness.

Does the use of comedy strengthen a political musical’s message?

To cast your vote, visit our online ballot.

“One Brief Shining Moment.” The politicization of Camelot in the wake of the John F. Kennedy assassination.

Camelot was a difficult show to get off the ground. Plagued by pacing problems, constant revisions, and health issues, the show opened to mixed reviews on Broadway despite the star casting of Richard Burton and Julie Andrews as Arthur and Guinevere. Librettist Alan Jay Lerner saw Camelot as a story of hope in difficult times:

For me, the raison d’être of Camelot was the end of the journey when Arthur has lost his love, his friend, and his Round Table and believes his life has been a failure. Then a small boy appears from behind a tent who doesn’t know the round table is dead and who wishes to become a knight. Arthur realizes that as long as his vision is alive in one small heart he has not failed. (Alan Jay Lerner, The Street Where I Live)

This proved to be a metaphor for the show itself. After extensive rewrites, Camelot reached a nationwide TV audience on the Ed Sullivan Show on March 19, 1961; suddenly ticket lines were around the block. The vision of Camelot became a reality, with a best-selling cast album and 4 Tony Awards.

Excerpt from Ed Sullivan's Best of Broadway Musicals DVD in The Julie Andrews Archives.

The assassination of President Kennedy in 1963 forever changed the American political and social landscape. Jacqueline Kennedy invited Life magazine to interview her about her husband’s legacy after his death. She reminisced about listening to the cast album of Camelot with JFK, and quoted a lyric now irrevocably tied to the memory of the Kennedy administration:

Don’t let it be forgot/That once there was a spot

For one brief shining moment /That was known as Camelot.

By comparing Kennedy’s time in office to the fictional ideal of King Arthur and his Round Table, Jackie Kennedy reinforced the idea of JFK’s reign as uniquely perfect, setting an unachievable bar for all presidents to come. “There’ll be great presidents again… but there’ll never be another Camelot,” she said. Heading into the 1960s, the Civil Rights movement, and the Vietnam War, the idea of the Kennedy administration as Camelot became cemented into the American mindset.

Jackie Kennedy’s framing of Camelot as a parallel for pre-1963 America tied her husband’s legacy to an idealistic fairy tale. This was certainly something Camelot’s authors, actors, and director never envisioned.

Is it appropriate for a public figure to use a popular Broadway musical to advance their political legacy?

To cast your vote, visit our online ballot.

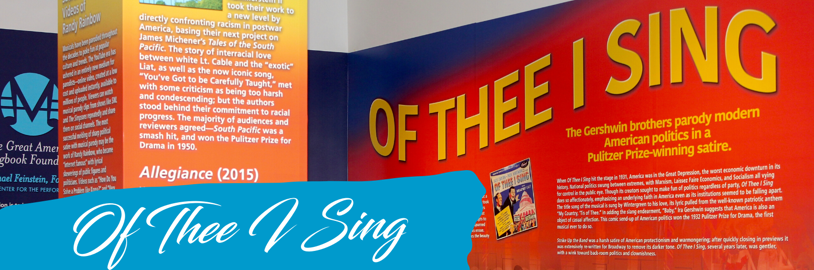

“Piddle, Twiddle, and Resolve.” 1776’s unsentimental look at America’s founding was embraced by a cynical public.

As America’s bicentennial approached, the U.S. was experiencing social turmoil. With heated conflicts over the Vietnam war, racial equality, and globalism, a musical about the Declaration of Independence seemed an unlikely hit. Yet Sherman Edwards and Peter Stone’s 1776 was well-received on both political sides—hippies and hardliners alike felt that the show spoke to what America is, or should be. Three years on Broadway and a later film adaptation established 1776 as the most popular history musical until Hamilton in 2015.

Sheet music from "1776": the Ray Charles Collection housed in

the Great American Songbook Foundation's Archives

Highlights from the 2016 City Center Encores! production of Sherman Edwards and Peter Stone's Tony-winning musical, 1776.

How did a musical about American politics manage to be all things to everyone? While the authors of the show were liberals, 1776 was hailed as a patriotic triumph by conservatives, receiving an invitation to perform at the White House from President Nixon. In describing the enthusiasm for the play by both Nixon’s government and radical liberal activists, librettist Peter Stone wrote,

“Had they seen the same play? Of course. What they had both experienced was the birth of their nation. One group believed that the American revolution had been fulfilled; the other was equally convinced it had not, but was determined to continue their struggle to fulfill it now.”

In the chaos of the late 1960s, Americans wanted to see the best in themselves. Conservatives believed the nation was conceived as a perfect union and remained so despite modern criticism. Liberals embraced the spirit of the Revolution and saw themselves as the true inheritors of the American ideal of rebellion. In this context, 1776 inspired hope for a broad audience during one of the most divided periods in U.S. history.

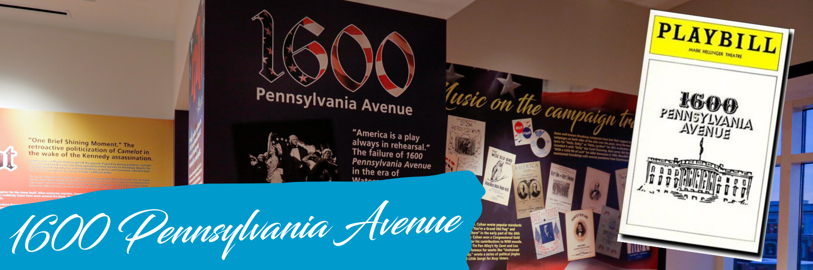

“America is a play always in rehearsal.” The failure of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue in the era of Watergate

When two giants of the American stage collaborated on a musical about the presidency, it seemed like a sure success. Leonard Bernstein, one of the most talented composers of all time, and Alan Jay Lerner, author of My Fair Lady and Camelot, teamed up to present a play-within-a-play looking back at America’s problematic history. Lerner imagined 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue showcasing the U.S. as “a play in rehearsal”—a small cast of actors performed the roles of all the featured presidents, first ladies, and African American servants. Each dropped in and out of character to offer commentary and criticism on the issues of each time period.

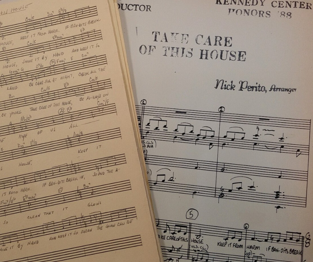

From the Ray Charles (arranger) collection: 1988 Kennedy Honors arrangement of

"Take Care of This House" from "1600 Pennsylvania Avenue"

Cynthia Erivo and the National Symphony Orchestra led by Gianandrea Noseda perform "Take Care of This House", from Leonard Bernstein's musical, 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. Video provided by The Kennedy Center.

The show was a disaster. Attempts to present a black viewpoint came across as racist; jokes fell flat; and political points were too heavy-handed. The bitter tone of 1600, combined with scripting missteps and a disorganized structure led a New York Times reviewer to call it “bleak and patronizing.” While motivated by a desire to address issues of political corruption and racial inequality, Lerner and Bernstein undermined their own goals by presenting a confusing, tone-deaf, and unsatisfying work. Though a number of songs have become popular in recent decades, 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue closed within a week of its Broadway opening in 1976.

Musicals and Campaigns

Some well-known Broadway composers have lent their support to political campaigns on both sides of the aisle over the years. Jerry Herman rewrote the lyrics for “Hello, Dolly!” as “Hello, Lyndon!” for LBJ’s re-election campaign and recorded it with “Dolly” star Carol Channing. Alan Lerner did the same, rewriting “With a Little Bit of Luck” for Adlai Stevenson in 1956. Meredith Willson maintained friendships with several presidents from Eisenhower to Reagan.

George M. Cohan wrote popular standards such as “You’re a Grand Old Flag” and “Over There” in the early part of the 20th century. Cohan was awarded a Congressional Gold Medal for his contributions to WWI morale. In 1956, Tin Pan Alley’s Hy Zaret and Lou Singer, famous for works like “Unchained Melody,” wrote a series of political jingles titled Little Songs for Busy Voters.

Have you ever seen a musical that changed your way of thinking about a political or social issue?

Tell us about it via our online ballot!

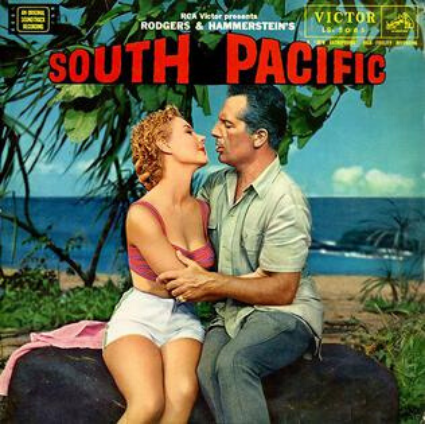

South Pacific (1949)

Having revolutionized the American musical theater with Oklahoma! and Carousel, Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II took their work to a new level by directly confronting racism in postwar America, basing their next project on James Michener’s Tales of the South Pacific. The story of interracial love between white Lt. Cable and the “exotic” Liat, as well as the now iconic song, “You’ve Got to be Carefully Taught,” met with some criticism as being too harsh and condescending; but the authors stood behind their commitment to racial progress. The majority of audiences and reviewers agreed—South Pacific was a smash hit, and won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1950.

Allegiance (2015)

Veteran actor and social media star George Takei partnered with composer-lyricist Jay Kuo to create this musical based on Takei’s childhood experience as a Japanese American confined to an internment camp in World War II. While the show itself received mixed reviews, its focus on the history of government-sponsored racism during the war brought attention to an era in U.S. history often treated with unquestioning admiration and an assumption of American rightness. Like many political musicals, Allegiance challenges its audience to examine its definitions of patriotism in the context of problematic U.S. history.

Hair (1968)

Hair: The American Tribal Love-Rock Musical is the quintessential show of the late 1960’s. The first true “rock musical,” Hair shocked audiences with its open themes of drug use, the sexual revolution, and onstage nudity as it captured the counter-culture of the Vietnam era. With a multiracial cast, creators Gerome Ragni, James Rado and Galt MacDermot confronted American racism head on in songs like “Dead End,” and “Colored Spade.” Its focus on highly political topics like environmentalism, pacifism, and spirituality gave Hair a lively energy that led to rave reviews across the political spectrum.

Dearest Enemy (1925)

This first collaboration between the legendary Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart was a historical musical based on real events of the Revolutionary War. In Dearest Enemy, New York Quaker Mary Lindley Murray and her daughters save the Revolutionary army by hosting the British general Howe and his troops at her home, distracting them with wine, cake, and flirtation long enough for the Americans to escape. This uncomplicated and romantic show was an early example of the theme of patriotism played out on a Broadway stage. The pair later wrote a political satire musical, I’d Rather Be Right, in 1937.

Bloomer Girl (1944)

A 1944 look back at women’s rights, Bloomer Girl tells the story of Evelina Applegate, an independent woman who rejects hoopskirts in favor of the far more comfortable “bloomers.” Set during the Civil War, this musical by E.Y. Harburg and Harold Arlen also touches on themes of civil rights and the abolitionist movement. Harburg used American history to delve more deeply into current social issues than many of his contemporaries; in a later work, Finian’s Rainbow, Harburg and writer Fred Saidy returned to some of these topics using a more fantasy-based setting.

Cabaret (1966)

While Cabaret takes place in 1930’s Berlin, its relationship to American politics is unquestionable. The theme of apathy plays out in the characters’ attemps to go on with their lives as Hitler’s fascist regeme rises to power. Many productions highlight Cliff’s rejection of apathy, implying that the characters in Berlin are likely to meet death at the hands of the Nazis. Hal Prince’s original Broadway production featured a mirror reflecting the audience, making them guilty bystanders to the atrocities to come. At the height of the Civil Rights movement in 1966, Cabaret drew a clear a parallel between the show’s German brownshirts and modern American brutality against people of color.

The Viral Videos of Randy Rainbow

Musicals have been parodied throughout the decades to poke fun at popular culture and trends. The YouTube era has ushered in an entirely new medium for parodists—online video, created at a low cost and uploaded instantly, available to millions of people. Viewers can watch musical parody clips from shows like SNL and The Simpsons repeatedly and share them on social channels. The most successful melding of sharp political satire with musical parody may be the work of Randy Rainbow, who became “internet famous” with lyrical skewerings of public figures and politicians. Videos such as “How Do You Solve a Problem like Korea?” and “Very Stable Genius” (parodying The Sound of Music and The Pirates of Penzance, respectively) rely on listeners’ familiarity with and affection for musical theater for its extra punch of humor.

Special Thanks to Our Exhibition Team and Subject Advisors:

- Archivist, Lisa Lobdell, Great American Songbook Foundation

- Exhibit development by Cathy Hamaker

- Subject advisor, Dominic McHugh, University of Sheffield

- Subject advisor, Elissa Harbert, DePauw University

- Graphic design and layout by Hill Design Service

- Graphic production and installation by Blue Ash

- Director of Programs, Renée La Schiazza, Great American Songbook Foundation

If you enjoyed this exhibit, borrow a traveling 4-panel version for your school, library, community center or cultural institution.

Please visit our Traveling Exhibit Page to learn more.