Bringing Mitzi Gaynor and Billy May’s “Let Go” Back to Life on Stage

October 24, 2025

By: Dr. Daniel Henderson

Associate Professor of Music, BYU-Hawaii

Director, BYU-Hawaii Studio Orchestra

Way out on the beautiful tip of the North Shore of Oahu, on the small college campus of BYU-Hawaii, we’ve been up to something special. We’ve built our own Studio Orchestra—a 48-piece hybrid between a jazz big band and a symphony orchestra, with jazz/pop singers and dancers fronting the stage. And we are devoted to restoring and performing music from the Golden Ages of Hollywood and Broadway, direct from the original manuscripts. Almost everything we perform has never been published, and much of it has never been performed by any other orchestra since the original recording sessions.

We specialize in the music of Ella Fitzgerald, Nat King Cole, Frank Sinatra, Johnny Mercer and the Pied Pipers, Bing Crosby and Rosemary Clooney, and the Golden Age of Kiddie Records—think Bugs Bunny, Mickey Mouse, and Bozo the Clown. We’ve performed music from archives and libraries around the country, including the Library of Congress, the Capitol Records Manuscript Collection, and more. (We’ve posted high-quality videos of most of our performances on our YouTube Channel - Jazz at BYU-Hawaii if you are interested!)

We’ve learned a lot in the process. As an educator, I’ve discovered something particularly valuable along the way: when we restore a piece of music from the original manuscripts, we have a chance to do something far more interesting than just PERFORM it. We can learn to THINK like the original artists did. Once we start to ask the same questions they asked, we can learn to strategize, problem-solve, and be intelligently creative like they were.

Or put it this way: as their professor, I can teach my students not just to perform this special music, but I can use it to help them develop the tools and confidence to make their own smart decisions as they build their own performing and teaching careers.

Without a doubt, one of the most thrilling pieces we’ve performed is “Let Go,” which is just one of hundreds of scores in the Mitzi Gaynor collection at the Great American Songbook Foundation in Carmel, Indiana. “Let Go” was the opening number of Mitzi Gaynor’s Emmy-winning 1969 television special (titled “Mitzi’s 2nd Special”). It featured the best of the best: the singing, dancing, and entertaining of Mitzi Gaynor and her cast, the costumes of Bob Mackie, choreography by Danny Daniels, vocal arrangements by Bob Alcivar, and musical arrangements by the man I’m finally writing a book about: my mentor, hero, and friend, the great Billy May.

Here is Mitzi’s performance of “Let Go”:

When we were preparing “Let Go” for our April 2025 performance, my students and I did a lot of brainstorming, and we asked a lot of questions. Let me share three of these questions with you to illustrate how we learned to think like the original creators and performers

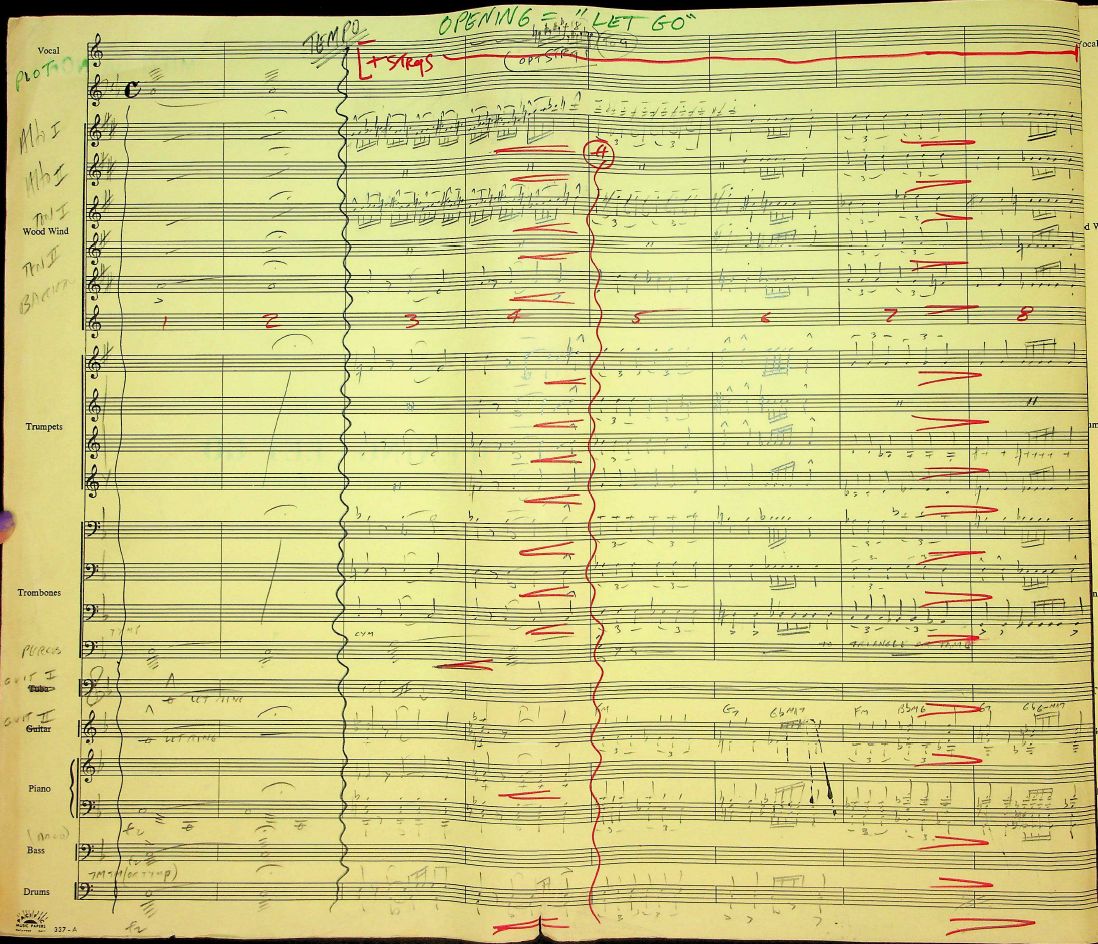

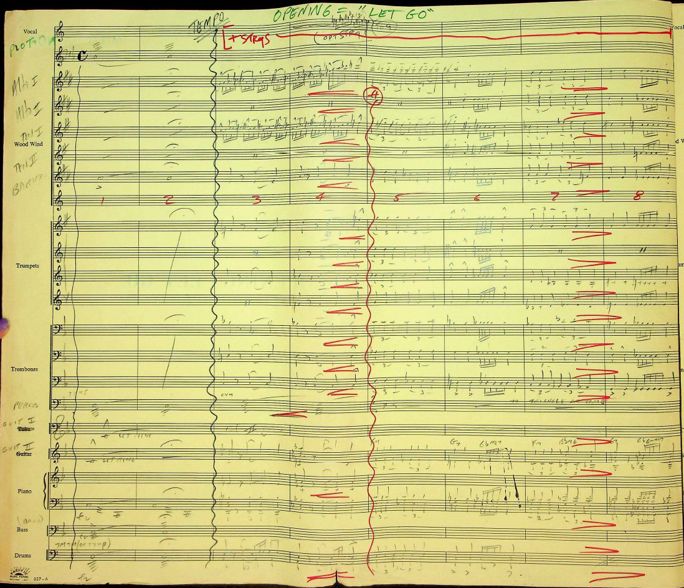

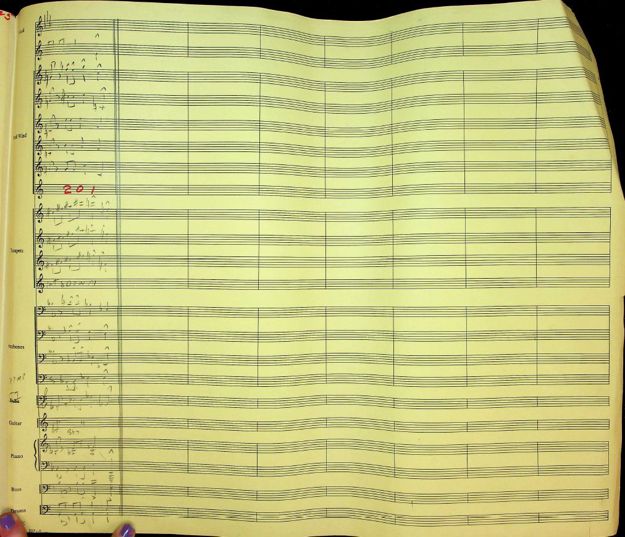

First question: what’s the purpose of the short musical introduction? Take a look at Billy May’s score:

But use your ear to compare how it’s performed in Mitzi’s special:

Notice the difference? Billy wrote a six-bar intro, but they only played the first four.

Why? And why does it matter? Well, it seems Billy’s purpose for the intro boils down to this: start with a flash bang of excitement, then decrescendo and bring it way down for the men’s vocal entrance. He gave them two bars to flash, and four bars to descrescendo. But in rehearsal, the men were already in place and ready to go after only two, so those last two bars became unnecessary.

So, should we do the same? Should we feel obligated to “be true” to the original? If so, which is the “original”—the 6-bar score, or the 4-bar performance? I think the right answer is this: neither. Rather, I think Billy would advise us to be true to the original principle that guides his thinking: Let the intro be as long as it needs to be for the men to be ready. If you need six, use six. If you’re ready in four, use four.

“Let Go” was the opening of our own concert, and we wanted to start with a bang of our own. Instead of already being on stage, our guys decided it would be exciting to start out of sight in the wings, and then burst onto the stage with my downbeat, run to their lighted spots, flex and flirt for a moment, let the crowd calm down, and then sing. This needed six bars, so we restored those two bars that had been cut. Here’s the opening of our concert:

“Let Go” ended up being so popular that we had to perform it again as an encore at the end of the concert. During the encore, the guys felt confident enough to get even get a bit wilder during their six-bar intro:

(Incidentally, I think it works better musically with all six bars since Billy’s harmonic cadence is more complete and more satisfying, but that’s not as important as the other questions.)

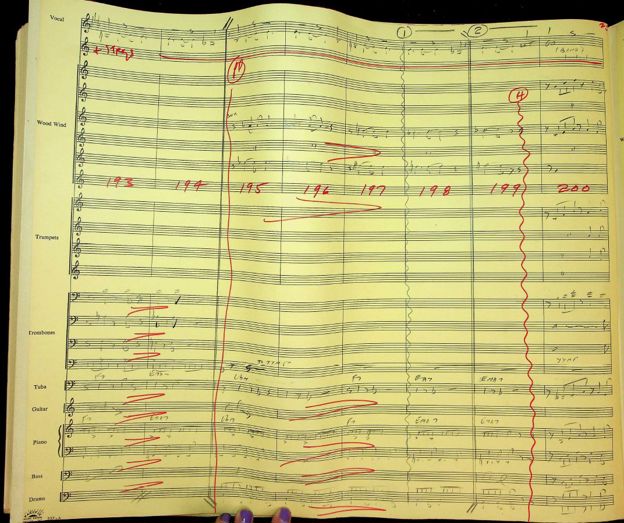

Second question: what about the ending? There’s an interesting problem here. Take a look at Billy’s original written ending:

But that’s not what they actually performed. Listen to the new ending:

It’s quite different. Why’d they change it?

Two reasons, I’d say: First, to give Mitzi’s last words, “Let go,” time to ring out and be heard clearly. Billy’s original written ending jumps in too fast, allowing Mitzi’s last word only an 8th note of space before the band comes barging back in. The new ending allows a full two beats of open space for her words to ring—far better and far clearer.

Second, the tone and mood of the endings are quite different. The original ending is kind of fun and syncopated, it’s very much in a major key, and it’s a bit cheeky. The new ending means business, sports a flash of minor key, and conveys strength and power. All things considered, the new ending is a better fit. They likely changed it after the first full orchestra rehearsal.

But when we were preparing our version at BYU-Hawaii, we didn’t have the score or parts for the new ending. We only had the original ending with its original problems. Since it was too late to scan and incorporate the new ending, we had to find a middle-ground fix. We tried a variety of options in rehearsal. None were great. Finally, we decided to just cut out its first two notes. This at least gave our singer’s final “Let go” more space to ring. Next time I’ll incorporate the new ending. But here’s how it sounded with our simple revision:

Final question: What about the music when Mitzi is descending onto the stage in that slow-moving elevator? There's 25 seconds of instrumental music allowing her to descend, walk down the ramp toward the camera, show off that incredible sheer Bob Mackie dress (front, side, and back), and finally get ready to sing. Here’s her intro:

What should we do? We don’t have a Mitzi Gaynor elevator at BYU-Hawaii. And our singers only have about five feet of depth at the front of the stage, so we can’t possibly recreate the movement. This was an important question: should we be practical again and just cut out some of this music since our cramped space won’t let us recreate all of this?

Easy answer: No way! Are you kidding me?!

Has any singer ever stepped on stage to a more thrilling musical introduction than this? Billy May was made for moments like this: to make Mitzi the queen of fashion, fun, and sex appeal before she sings a single word. A talent like Mitzi’s, and a dress like Bob Mackie’s, demands music that is nothing less than joyful, dazzling perfection.

And so, we switched out thinking: This musical moment is so incredibly good we’d be fools to cut it. We needed to find a way to not only fill those 25 wordless seconds with action, but to make it so entertaining that the audience would cheer and scream and fill the hall with a jolt of rock-star energy.

During one of our brainstorms, Brianna came up with the idea to burst into the back of the hall behind the audience. Then, in her bedazzled gown, the spotlight would find her as she danced down the aisle, up the stairs, and onto the stage. She practiced the timing so that she was in place at center stage right in time to sing. Here it is:

But for the encore, there was no time for Brianna to get out into the lobby again (nor for her and Steven Tee to change back into their same costumes). No matter. She came on from the wings, spontaneously egging the crowd on with her natural charm, humor, and a slow booty shake—just listen to the crowd roar!

Arrangers juggle a lot of technical data, they solve a lot of problems, and they make it easy for singers to sound their very best. But at their very best, great arrangers create great MOMENTS. Moments that thrill, moments that change us, moments that puncture our shield of indifference, moments we never forget. This is one of those moments.

A blog post is no place to get into the nerdy technicalities of Billy’s score, so I won’t go into detail here. But for certain, there’s an Honors thesis waiting to be written by some aspiring young arranger. Call it “38 Seconds to Stardom: Setting Up Mitzi’s Gaynor’s Iconic Entrance in ‘Let Go!’” It will reveal a master arranger at the peak of his craft. It might uncover Billy May’s command of harmony and modulation as an emotional and storytelling tool, from the shock and suspense of the sudden dominant-V timpani roll in F minor, through surprise modulations to G Major (the very moment the elevator becomes visible), then to Bb Major (the very moment she takes her first step off the elevator), to a sizzling simmering-down in D minor (the very moment she turns to the side, allowing us to see her profile in Bob Mackie’s fantastic gown). It might explore the orchestration and the ways Billy uses each instrument for maximum power and groove. It might explore volume and dynamics and the way Billy creates one large crescendo from the moment the elevator appears to the moment she arrives at the front of the stage, pulling all the way back to near-silent the moment she opens her mouth to sing. She is captivating in every way, and Billy May shines his brightest musical spotlight on Mitzi Gaynor in this unforgettable performance.

During this process, our students fell in love with Mitzi, with the whole performance, with the music, with the choreography. And you can tell when students have bought in to something with 100% of their heart and soul. Here’s one final excerpt showing the admiration and dedication of every member of our orchestra to the original performers (watch out for dancing trumpet players!). We thought of our performance as a love letter to them:

One final thought: This is just one arrangement from one collection. There’s a whole massive library of music in the collections at the Great American Songbook Foundation just waiting to be performed. Some of them are phenomenally good. Dive in! I hope this article has been helpful and inspiring, and I can’t wait to hear from people around the world who are bringing this amazing music back to life, on a stage, where it belongs.

This post was contributed by a guest author. The ideas and opinions shared are their own and do not necessarily represent those of the Great American Songbook Foundation.